When my firstborn told us a few months ago that they were nonbinary, their dad and I were a bit surprised, but not really. They have struggled for the past few years with their identity and some mental health challenges–which have only been exacerbated by a pandemic.

Above all, we want them to feel happy and secure and loved–always. So we were supportive and nonplussed when they told us they were changing their pronouns from she/her to they/them and shared with us that they have “fem days” and “masc days” and would plan on dressing and acting according to what felt natural at the time. But there was one part of the news that was a bit difficult for me: their decision to take a new name.

What’s in a name

When we were expecting, like many other parents-to-be we poured over baby name books, tried endless combinations of first-plus-middle, drew on our parents’ and grandparents’ ethnic heritages (in our case that was Hungarian and Irish) and ruled out anything that could be rhymed or twisted into something used to tease or mock or bully.

Ironically, we decided not to learn their sex ahead of time, instead narrowing our list down to two boy names and two girl names. Perhaps even more ironically, their dad nixed my top boy pick–Morgan–because he said it seemed too feminine. Morgan Fairchild, he said. Morgan Freeman, I retorted. We eventually decided we would wait until the delivery, and figure out which of the names just seemed right.

When our daughter was born, we took one look at their face and immediately decided on an Irish first name, with a middle name that coincidentally was a last name in both family’s lineages. It seemed perfect, sounded perfect, looked perfect. And even now when I think of it, it’s stunningly beautiful. Though now more so in a wistful, nostalgic way.

Changes can be hard on everyone

After our now-seventeen-year-old changed their preferred name–not legally just yet, but in practice–their birth name became what’s referred to as a deadname, a former name no longer used as it lacks consent.

Transgender and nonbinary supporters argue that repeated deadnaming, whether on purpose because of refusal of acceptance or by otherwise supportive friends and family members who won’t, can’t or refuse to use a new name–can be viewed as both a microaggression and a failure to allyship. I got it, I get it.

Still, I winced a little the first few (or few dozen) times I used or thought about the new choice, even though I respected and appreciated the thought that went into it, and my heart swelled to think of the lightness they said it brought them, which had been missing for far too long. Yet I couldn’t get past thinking of their birth name as something personal, special, a gift we bestowed on them when they entered the world.

And I wasn’t alone. Scrolling through the feed of a Facebook group for nonbinary parents to which I belong, I often saw posts from moms and dads who considered themselves stalwart allies for their enbys, yet couldn’t stop feeling sadness at relinquishing a name first written in Sharpie on a hospital bassinet label, then embroidered on a baby blanket tucked into a stroller, inscribed on a kindergarten diploma, and used to sign a third-grade watercolor masterpiece.

Realizing there was more to relate to here

But how many of us walk around with first names that we actually like, that we would have chosen for ourselves? I certainly don’t. When I was around ten years old I remember creating a list of names I preferred instead.

In junior high school French class I was thrilled to be able to select a different moniker; one year I was Gisèle, the next I was Geneviève. I never would have selected Kelly, nor did I think about it as a significant or meaningful act by my parents. What’s in a name, indeed.

This got me thinking about other gifts I attempted to bestow on my teenager when they were younger, which in retrospect now seem more like projections of what I liked or wished or wanted for them.

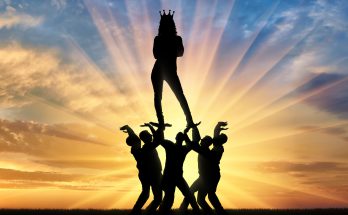

I signed them up for ballet, then jazz, then tap, then hip hop, because I wanted to share with them my love of dance. But it didn’t take. A theater kid all through high school, I encouraged them to audition for the school play, and when they were nervous about getting on stage I suggested the stage crew. They weren’t interested in either. Turns out, like the gender assigned at birth and the name we gave them, these activities didn’t suit them.

I remembered a parenting quote I heard years ago that’s attributed to Lebanese poet, writer and artist Kahlil Gibran. I’m paraphrasing, but the gist of it is also a metaphor for how a nonbinary child feels about their birth name. Your children don’t belong to you. You merely get to borrow them for a while.